by JOHN ROBINSON • artwork by GARY LUCY

The Alert was only a few miles above Hermann when it happened. A lookout at the bow of the boat spotted a sawyer at the edge of the channel near Fisher’s Landing. He pointed to it so the captain would see.

Attached to submerged trees, sawyers are limbs that stick out of the water, pinned against the swift current. The captain already had seen it, since sawyers are red flags, triggers waiting to spring a submerged trunk like a mousetrap. Any captain would have seen it, because that’s how they become captains. They see all the obstacles atop the water. But the good ones, the captains who endure, they know what’s under the water.

“Like all early-day boats on the Missouri River, she was a side wheeler,” wrote E.B. Trail, one of the Missouri River’s foremost steamboat historians. And she ran “an irregular trade on the Missouri.” That may have been the Alert’s undoing.

She had beat the odds so far, five years old and still going strong, built in Pittsburgh the same year Sam Clemens was born, 1835. But she had entered a river where most steamboats wouldn’t reach their third birthday. On the Ohio River or the Mississippi, she could chug in relative safety at five or six miles an hour and provide useful service for a dozen years, maybe more.

But this was the Missouri.

The captain steered the boat safely past the sawyer and rounded the tight bend into the narrow channel when he felt the jolt. His heart sank. The Alert had struck a snag. He had evaded the snap of the sawyer, but snags are nature’s torpedoes, submerged trees that offer no warning before a collision punctures a wooden hull below the waterline. In minutes the river rushed into the gash and claimed another victim.

To the small fraternity of riverboat pilots whose two dozen boats braved the Missouri River in 1840, that spot became known as Alert Bend. Within the year, two more spots on the Missouri River would take their names from shipwrecks. And there would be more.

Highway 94 hugs the Missouri River like a belt. As I drove through its rollercoaster turns I didn’t worry about sawyers or snags, but kept an eye out for turtles and deer, until I turned south on Highway 19 at its uncharacteristically wide, straight-as-a-string approach to Hermann. My car crossed the brand new bridge, spacious and safe compared to the bridge it replaced, giving me the courage to take my eyes off the road and look to my right to absorb the view from this new span. Beyond my passenger window the river stretched toward the sunset in one shimmering ribbon, full, complete, self-contained, until it rounded out of sight. Even though I’d crossed the Missouri River into Hermann a hundred times before, today I paid closer attention to the river below. As we neared the Hermann bank, my car knew I would turn off the highway and drive up the steep hill to the top of a bluff that offers a loftier view of this magnificent stream that drains damn near half the Wild Wild West.

From my perch at the edge of the bluff, I watched a towboat push one single barge downstream. The barge contained a modest pyramid of sand, dredged from the river channel upstream. Best I could tell, the barge was headed to the closest depository for sand, and from there the sand most likely would be mixed with cement to become a highway or a dam or some other concrete monument to channelization.

Other than the sand barges, it’s rare anymore to see commerce on this river. A generation ago the barge traffic all but died out, same as the eagles that used this route for the same purpose: navigation and food.

Now the eagles are back. But the barges, except in rare cases, have followed the steamboats into history.

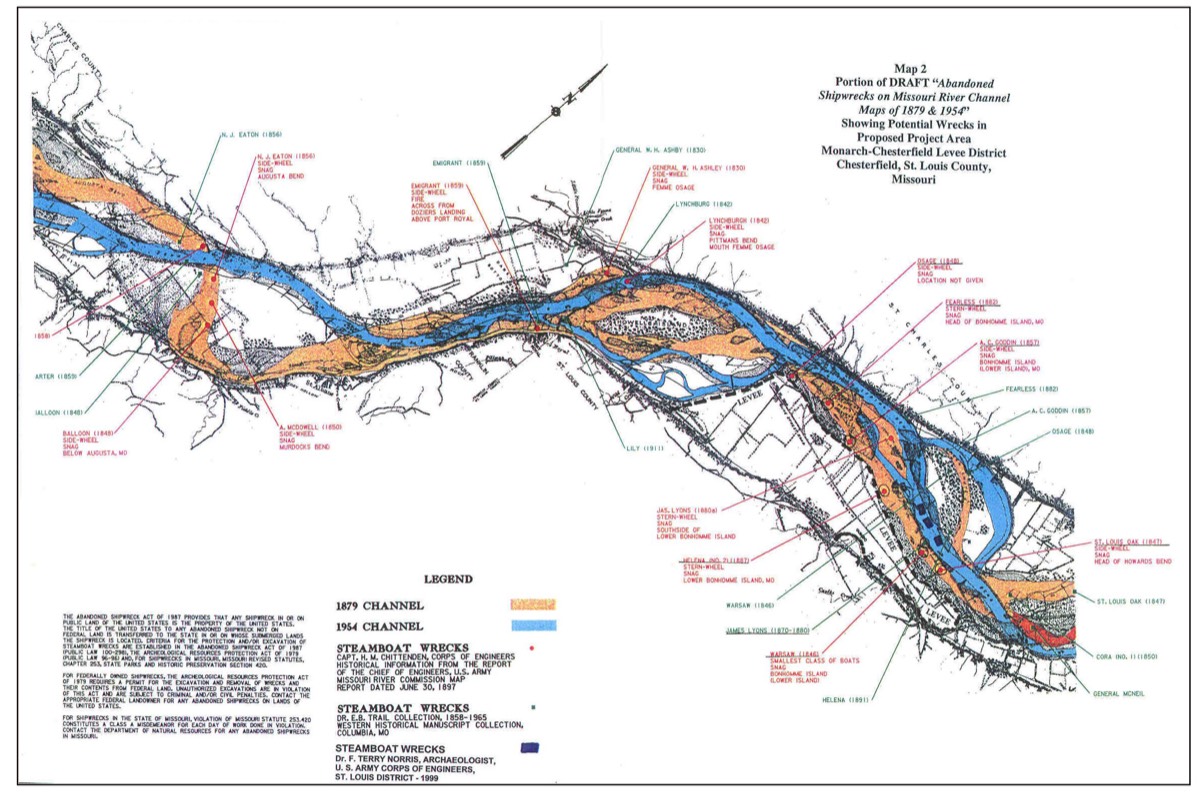

I grew up on this river. And so I’d heard the stories, how it was the first highway of westward expansion, how the steamboats came and went, ferrying pioneers on their first leg of a long journey west, leaving more than 300 shipwrecked hulks beneath the flood plain as tombs filled with enough provisions to satisfy a pharoah in the first millennium of afterlife.

My eyes followed the sand barge’s wake upstream, past the spot on the opposite bank closest to old Fisher’s Landing. It would take a tsunami to wet Alert Bend nowadays. Since the channel was straightened, the bend sits a half mile from the river under a billion tons of the finest soil in the heartland.

Back before the U.S. Corps of Engineers did their “levee best” to manipulate this river’s braiding channels into one navigable water course, the riverbed offered hundreds of short cuts, just like the Jack’s Fork. The only difference between today’s wild Jack’s Fork and the 1840’s Missouri was the volume of water, which made the Missouri navigable for big boats, and brought daring captains to thread their steamboats along tricky currents through tight bends, picking chutes on a guess, sometimes, past floes and eddies, around shallows and riffles, shoals and rapids with names like Devil’s Rake.

Looking upriver from the Hermann bluff, it’s hard to imagine 300 shipwrecks beneath these waters. But they’re there. I could almost see Sonora Chute. It was a cold February day in 1856 when Captain Bill Terrill ran his sidewheeler Sonora through ice floes near Portland, Missouri. At 363 tons, the Sonora was a good size, but her wooden hull was no match for the ice, and she sank. For years after that, the wreck of the Sonora was visible at low water. In 1916 her machinery and brass were removed, and finally, in 1940, the dredge Keokuk removed the wreckage.

As a kid I remember warm summer evenings on the bluffs above the river as it moved silently through the darkness past my Jefferson City home. Back then it was easier to find total darkness, away from star-erasing pollution caused by streetlights and security lamps and sprawling subdivisions. I could sneak to the edge of town and find a clear vantage point where the heavens would entertain me with infinite vastness, rewarding my patience with a shooting star across the Milky Way. But I never waited long before a lightsaber would stab the black night, waving low across the river valley, focused razor-sharp from the bridge of a towboat, its concentrated beam of white light swinging from one fix to the next, marker to marker, buoy to bridge to bank and back again, bright enough to make a new moon full.

Back when I was a kid, riverboat spotlights were common as fireflies. In the deep darkness these powerful beams helped show the way for gigantic rafts formed when daredevils lashed big barges together, two across, four barges long and filled them with the harvest from America’s breadbasket and rode them from Omaha and Sioux City and Bismarck, pushing their cargo day and night down to the Mississippi.

Barge traffic finally died out when engineers dammed the river in the Dakotas. The dams do their best to control flooding in the spring, and they do a better job of offering recreation in the summer. But they also withhold the autumn waters that ferried the grain harvest to St. Louis and New Orleans and St. Paul. So nowadays the grain does what the travelers do: take the highways, and a rail route or two. And Missouri River barges join the steamboats as relics of our past, pictures in American history books, alongside trail bosses and buffalo and locomotives. Steamboat whistles—once common as the caws of crows—are fading memories.

Oh, steamboats could still ply these waters. At least I believe they could. But my enthusiasm for river travel on the Missouri is not shared by people who know more than I do about such things. Riverboat captains have a definite opinion about the river. Their opinion aligns with their views about jumping off cliffs, or going to the dentist, or sticking fingers into a meat grinder. Avoid it.

A dozen years ago Cheryl and I were on the Delta Queen, headed from St. Paul to St. Louis on a seven-day sojourn to see the Mississippi from the inside out, like Sam Clemens suggested. On the second night, we donned our best attire to dine with the captain. After the appropriate ice breaker chit chat, I asked him directly, “Why don’t you take this boat up the Missouri?” He looked as if I had summoned the Devil to dine with us.

“Dangerous river,” he drew out his words for emphasis. “Swift current, treacherous bends. My steamer will not travel up the Missouri.” Captain John Davitt was true to his word. With one exception in the past two decades, when a steamboat visited St. Charles, the royal sisters—Mississippi Queen, American Queen, Delta Queen—avoided the waters of the Missouri River.

You can’t blame them. The river has a reputation for turbulence. With a current eclipsing six knots in spots, and a billion wing dams channeling the water into narrow slaloms and whirling pools, it’s an adventure to pilot a wedding cake down the river.

Wedding cake. That’s a nickname for old riverboat steamers. One look at their structures, and the name is obvious. And standing on Hermann’s west bluff, I knew where there was an extensive photo collection of riverboat wrecks, just downhill at the German School Museum. I headed down the hill to see what a wedding cake looks like after the bride crashes into it. Hundreds of photos fill the museum’s River Room, many showing steamboats in the agonizing throes of death. I spent the afternoon paging through the giant photographs, wrecks dashed against the rocks and drowned in the river, proud old riverboats that knew their days were counted in weeks and months when they entered the treacherous currents and snags of the Missouri River. These old shipwreck photos kept me captive, evoking the same human curiosity that causes traffic to slow to a crawl as gapers pass a car wreck.

Sufficiently spooked by the dangers of travel, I drove home.

Next day, Highway 40 delivered me through the pastoral pleasance of Howard County, and at Franklin I turned north toward another new bridge, this one crossing the Missouri River at Glasgow.

I drove along the banks of this town whose charms are regularly overlooked. Like the other riverports up and down the Missouri, Glasgow’s history extends to the beginnings of westward expansion. Its oldest homes saw the early settlers clutching the handrails of steamboats, felt the heat from the Civil War, and survived to flavor the town’s hilltops. Nearer the river, the

business district maintains the feel of the 19th century, including the oldest continuously-operated soda fountain west of the Mississippi at Henderson Drug Store.

A few years ago the town inherited an old barge from upriver, its decaying superstructure betraying its sinful past. It once served as the old St. Jo Casino. Today, it’s tied to wild trees along a muddy riverbank, hoping to rekindle its old spark, sans slots. Alas, recent floods loosed a barrage of trees and debris down the river, big wooden torpedoes that helped deep six the old barge. So it sits half submerged at the edge of the bank, choking a stump, bobbing in the rushing brown water, calling for help that can’t come in time.

It happened before, not far from here, but long ago, on September 17, 1840.

The Euphrasie was a sidewheeler named for the wife of owner George Collier, and it did a brisk business transporting hemp and tobacco from 11 tobacco stemmeries and factories around Glasgow. The boat left town headed downstream loaded with 150 bales of rope and bagging, and at least $14,000 worth of insurance on the 71 hogsheads of tobacco on board. Four miles downstream, the Euphrasie struck a snag and sank in what became known as Euphrasie Bend. Salvage efforts recovered the boat’s furniture, and even the engine, which was installed in the steamer Oceana. Nobody died, but the insurance settlement claimed a victim on shore. The Glasgow Marine Insurance Company went bankrupt covering the loss.

Euprasie Bend is the graveyard for several other boats, including the Chariton, the Dart, the Amelia, the J.H. Oglesby, the West Wind and the Annie Lee.

Not far upriver, Malta Bend might be the most-repeated name of a shipwreck bend on the Missouri. Since that wreck, the river has changed course, and the bend no longer exists, although the town named after it is still there. Back in August 1841, Captain Joseph W. Throckmorton was piloting the steamer he originally designed as a comfortable excursion boat. Its cabins even had innerspring mattresses. But Throckmorton had adapted the boat to the fur trade, and on this day, he was guiding the Malta around a sweeping bend two miles above Laynesville when the boat struck a snag and sank.

With so many wrecks on this river, why did people even get on these boats? According to Captain James Kennedy, who piloted boats on the river during this period, “Loss of life is rare on rivers save in the case of an explosion.” Like the Malta, most sinkings were caused by snags. The Malta sank in a little more than a minute, but resting in only 12 feet of water, its upper decks stood above the waterline, where passengers waited to be rescued. Nobody died in the Malta wreck, although the boat and cargo were a total loss. That was a typical shipwreck when a boat hit a snag: the boat found a shallow bottom, and passengers found the upper deck.

So passengers braved the odds. And they did it in style.

One captain who also enjoyed a good poker game was the legendary William Rodney “Bill” Massie, who usually beat the odds as a pilot on the river and as a player at the card table. After he retired from the river, his luck took a strange twist on August 2, 1876, when he sat at a poker table in Deadwood, South Dakota, with Wild Bill Hickok and two other players. On this day Hickok’s back wasn’t to the wall, as was his custom, and Massie apparently refused to change seats with Hickok not once, but twice. Not only that, but Massie was winning and Hickok was losing. In Hickok’s last game, as Massie laid down his winning hand, Wild Bill took an assassin’s bullet in the back of his head. The bullet exited through Hickok’s cheek and lodged in Massie’s wrist. Wild Bill’s hands still clutched his last poker hand with two pair—aces and eight—known to modern poker players as the dead man’s hand. Massie carried that bullet in his wrist for 34 years, and took it to his grave in St. Louis’ Bellfontaine Cemetery.

Massie’s good fortune at the poker table was surpassed only by his skill on the river. He could read the signs on the water’s surface—ripples, colors, stream lines—and tell whether they hid snags or obstacles, and he knew how they changed depending on weather. He memorized the river like no pilot before or since. He could navigate tricky turns like Providence Bend rounding the southwest edge of Boone County, and Plowboy Bend just below that, where the sidewheeler Plowboy sank in 1853. The townspeople of Sandy Hook built the first house in town from the ship’s cabin.

Other pilots paid Massie so they could follow his course, and sometimes he’d lead a string of six or eight boats. In 60 years of piloting, Massie sank only one boat, when the giant sternwheeler Montana hit the Wabash Bridge at St. Charles.

“Steamboat Bill” Heckman tells a story about Massie’s Montana and her sister ship, the Dacotah, in the December 30, 1939 issue of Waterways Journal. When Captain John Gonsallis hit a stump in Providence Bend and sank the Dacotah in 1884, Massie sneered: “Did Gonsollas not know an obstruction as prominent as that stump in Providence Bend?” Gonsollas responded that the stump wasn’t near as prominent as the bridge where Massie wrecked the Montana, just three months earlier.

As the sun set on the steamboating era, those great riverboat captains must have seen the paradox: to compete with the railroads, they built bigger and bigger boats. But the big boats were not as agile on the wild Missouri River, unforgiving around the shipwreck bends.

The Alert was only a few miles above Hermann when it happened. A lookout at the bow of the boat spotted a sawyer at the edge of the channel near Fisher’s Landing. He pointed to it so the captain would see.

Attached to submerged trees, sawyers are limbs that stick out of the water, pinned against the swift current. The captain already had seen it, since sawyers are red flags, triggers waiting to spring a submerged trunk like a mousetrap. Any captain would have seen it, because that’s how they become captains. They see all the obstacles atop the water. But the good ones, the captains who endure, they know what’s under the water.

“Like all early-day boats on the Missouri River, she was a side wheeler,” wrote E.B. Trail, one of the Missouri River’s foremost steamboat historians. And she ran “an irregular trade on the Missouri.” That may have been the Alert’s undoing.

She had beat the odds so far, five years old and still going strong, built in Pittsburgh the same year Sam Clemens was born, 1835. But she had entered a river where most steamboats wouldn’t reach their third birthday. On the Ohio River or the Mississippi, she could chug in relative safety at five or six miles an hour and provide useful service for a dozen years, maybe more.

But this was the Missouri.

The captain steered the boat safely past the sawyer and rounded the tight bend into the narrow channel when he felt the jolt. His heart sank. The Alert had struck a snag. He had evaded the snap of the sawyer, but snags are nature’s torpedoes, submerged trees that offer no warning before a collision punctures a wooden hull below the waterline. In minutes the river rushed into the gash and claimed another victim.

To the small fraternity of riverboat pilots whose two dozen boats braved the Missouri River in 1840, that spot became known as Alert Bend. Within the year, two more spots on the Missouri River would take their names from shipwrecks. And there would be more.

Highway 94 hugs the Missouri River like a belt. As I drove through its rollercoaster turns I didn’t worry about sawyers or snags, but kept an eye out for turtles and deer, until I turned south on Highway 19 at its uncharacteristically wide, straight-as-a-string approach to Hermann. My car crossed the brand new bridge, spacious and safe compared to the bridge it replaced, giving me the courage to take my eyes off the road and look to my right to absorb the view from this new span. Beyond my passenger window the river stretched toward the sunset in one shimmering ribbon, full, complete, self-contained, until it rounded out of sight. Even though I’d crossed the Missouri River into Hermann a hundred times before, today I paid closer attention to the river below. As we neared the Hermann bank, my car knew I would turn off the highway and drive up the steep hill to the top of a bluff that offers a loftier view of this magnificent stream that drains damn near half the Wild Wild West.

From my perch at the edge of the bluff, I watched a towboat push one single barge downstream. The barge contained a modest pyramid of sand, dredged from the river channel upstream. Best I could tell, the barge was headed to the closest depository for sand, and from there the sand most likely would be mixed with cement to become a highway or a dam or some other concrete monument to channelization.

Other than the sand barges, it’s rare anymore to see commerce on this river. A generation ago the barge traffic all but died out, same as the eagles that used this route for the same purpose: navigation and food.

Now the eagles are back. But the barges, except in rare cases, have followed the steamboats into history.

I grew up on this river. And so I’d heard the stories, how it was the first highway of westward expansion, how the steamboats came and went, ferrying pioneers on their first leg of a long journey west, leaving more than 300 shipwrecked hulks beneath the flood plain as tombs filled with enough provisions to satisfy a pharoah in the first millennium of afterlife.

My eyes followed the sand barge’s wake upstream, past the spot on the opposite bank closest to old Fisher’s Landing. It would take a tsunami to wet Alert Bend nowadays. Since the channel was straightened, the bend sits a half mile from the river under a billion tons of the finest soil in the heartland.

Back before the U.S. Corps of Engineers did their “levee best” to manipulate this river’s braiding channels into one navigable water course, the riverbed offered hundreds of short cuts, just like the Jack’s Fork. The only difference between today’s wild Jack’s Fork and the 1840’s Missouri was the volume of water, which made the Missouri navigable for big boats, and brought daring captains to thread their steamboats along tricky currents through tight bends, picking chutes on a guess, sometimes, past floes and eddies, around shallows and riffles, shoals and rapids with names like Devil’s Rake.

Looking upriver from the Hermann bluff, it’s hard to imagine 300 shipwrecks beneath these waters. But they’re there. I could almost see Sonora Chute. It was a cold February day in 1856 when Captain Bill Terrill ran his sidewheeler Sonora through ice floes near Portland, Missouri. At 363 tons, the Sonora was a good size, but her wooden hull was no match for the ice, and she sank. For years after that, the wreck of the Sonora was visible at low water. In 1916 her machinery and brass were removed, and finally, in 1940, the dredge Keokuk removed the wreckage.

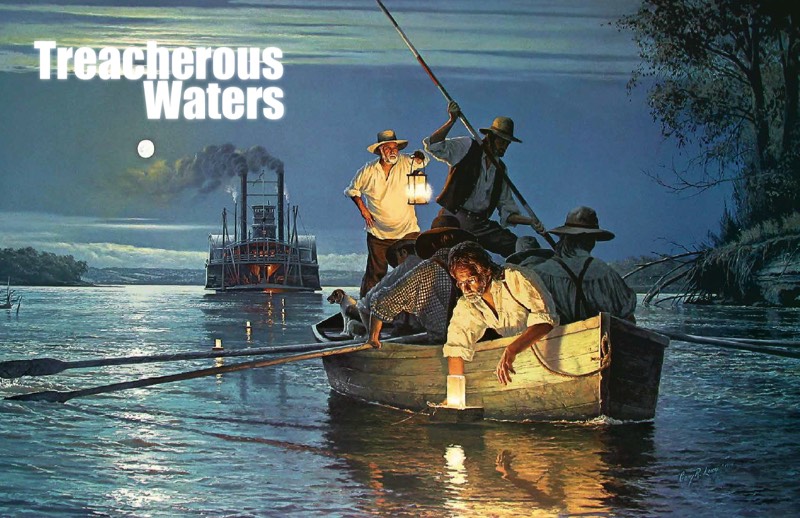

As a kid I remember warm summer evenings on the bluffs above the river as it moved silently through the darkness past my Jefferson City home. Back then it was easier to find total darkness, away from star-erasing pollution caused by streetlights and security lamps and sprawling subdivisions. I could sneak to the edge of town and find a clear vantage point where the heavens would entertain me with infinite vastness, rewarding my patience with a shooting star across the Milky Way. But I never waited long before a lightsaber would stab the black night, waving low across the river valley, focused razor-sharp from the bridge of a towboat, its concentrated beam of white light swinging from one fix to the next, marker to marker, buoy to bridge to bank and back again, bright enough to make a new moon full.

Back when I was a kid, riverboat spotlights were common as fireflies. In the deep darkness these powerful beams helped show the way for gigantic rafts formed when daredevils lashed big barges together, two across, four barges long and filled them with the harvest from America’s breadbasket and rode them from Omaha and Sioux City and Bismarck, pushing their cargo day and night down to the Mississippi.

Barge traffic finally died out when engineers dammed the river in the Dakotas. The dams do their best to control flooding in the spring, and they do a better job of offering recreation in the summer. But they also withhold the autumn waters that ferried the grain harvest to St. Louis and New Orleans and St. Paul. So nowadays the grain does what the travelers do: take the highways, and a rail route or two. And Missouri River barges join the steamboats as relics of our past, pictures in American history books, alongside trail bosses and buffalo and locomotives. Steamboat whistles—once common as the caws of crows—are fading memories.

Oh, steamboats could still ply these waters. At least I believe they could. But my enthusiasm for river travel on the Missouri is not shared by people who know more than I do about such things. Riverboat captains have a definite opinion about the river. Their opinion aligns with their views about jumping off cliffs, or going to the dentist, or sticking fingers into a meat grinder. Avoid it.

A dozen years ago Cheryl and I were on the Delta Queen, headed from St. Paul to St. Louis on a seven-day sojourn to see the Mississippi from the inside out, like Sam Clemens suggested. On the second night, we donned our best attire to dine with the captain. After the appropriate ice breaker chit chat, I asked him directly, “Why don’t you take this boat up the Missouri?” He looked as if I had summoned the Devil to dine with us.

“Dangerous river,” he drew out his words for emphasis. “Swift current, treacherous bends. My steamer will not travel up the Missouri.” Captain John Davitt was true to his word. With one exception in the past two decades, when a steamboat visited St. Charles, the royal sisters—Mississippi Queen, American Queen, Delta Queen—avoided the waters of the Missouri River.

You can’t blame them. The river has a reputation for turbulence. With a current eclipsing six knots in spots, and a billion wing dams channeling the water into narrow slaloms and whirling pools, it’s an adventure to pilot a wedding cake down the river.

Wedding cake. That’s a nickname for old riverboat steamers. One look at their structures, and the name is obvious. And standing on Hermann’s west bluff, I knew where there was an extensive photo collection of riverboat wrecks, just downhill at the German School Museum. I headed down the hill to see what a wedding cake looks like after the bride crashes into it. Hundreds of photos fill the museum’s River Room, many showing steamboats in the agonizing throes of death. I spent the afternoon paging through the giant photographs, wrecks dashed against the rocks and drowned in the river, proud old riverboats that knew their days were counted in weeks and months when they entered the treacherous currents and snags of the Missouri River. These old shipwreck photos kept me captive, evoking the same human curiosity that causes traffic to slow to a crawl as gapers pass a car wreck.

Sufficiently spooked by the dangers of travel, I drove home.

Next day, Highway 40 delivered me through the pastoral pleasance of Howard County, and at Franklin I turned north toward another new bridge, this one crossing the Missouri River at Glasgow.

I drove along the banks of this town whose charms are regularly overlooked. Like the other riverports up and down the Missouri, Glasgow’s history extends to the beginnings of westward expansion. Its oldest homes saw the early settlers clutching the handrails of steamboats, felt the heat from the Civil War, and survived to flavor the town’s hilltops. Nearer the river, the

business district maintains the feel of the 19th century, including the oldest continuously-operated soda fountain west of the Mississippi at Henderson Drug Store.

A few years ago the town inherited an old barge from upriver, its decaying superstructure betraying its sinful past. It once served as the old St. Jo Casino. Today, it’s tied to wild trees along a muddy riverbank, hoping to rekindle its old spark, sans slots. Alas, recent floods loosed a barrage of trees and debris down the river, big wooden torpedoes that helped deep six the old barge. So it sits half submerged at the edge of the bank, choking a stump, bobbing in the rushing brown water, calling for help that can’t come in time.

It happened before, not far from here, but long ago, on September 17, 1840.

The Euphrasie was a sidewheeler named for the wife of owner George Collier, and it did a brisk business transporting hemp and tobacco from 11 tobacco stemmeries and factories around Glasgow. The boat left town headed downstream loaded with 150 bales of rope and bagging, and at least $14,000 worth of insurance on the 71 hogsheads of tobacco on board. Four miles downstream, the Euphrasie struck a snag and sank in what became known as Euphrasie Bend. Salvage efforts recovered the boat’s furniture, and even the engine, which was installed in the steamer Oceana. Nobody died, but the insurance settlement claimed a victim on shore. The Glasgow Marine Insurance Company went bankrupt covering the loss.

Euprasie Bend is the graveyard for several other boats, including the Chariton, the Dart, the Amelia, the J.H. Oglesby, the West Wind and the Annie Lee.

Not far upriver, Malta Bend might be the most-repeated name of a shipwreck bend on the Missouri. Since that wreck, the river has changed course, and the bend no longer exists, although the town named after it is still there. Back in August 1841, Captain Joseph W. Throckmorton was piloting the steamer he originally designed as a comfortable excursion boat. Its cabins even had innerspring mattresses. But Throckmorton had adapted the boat to the fur trade, and on this day, he was guiding the Malta around a sweeping bend two miles above Laynesville when the boat struck a snag and sank.

With so many wrecks on this river, why did people even get on these boats? According to Captain James Kennedy, who piloted boats on the river during this period, “Loss of life is rare on rivers save in the case of an explosion.” Like the Malta, most sinkings were caused by snags. The Malta sank in a little more than a minute, but resting in only 12 feet of water, its upper decks stood above the waterline, where passengers waited to be rescued. Nobody died in the Malta wreck, although the boat and cargo were a total loss. That was a typical shipwreck when a boat hit a snag: the boat found a shallow bottom, and passengers found the upper deck.

So passengers braved the odds. And they did it in style.

One captain who also enjoyed a good poker game was the legendary William Rodney “Bill” Massie, who usually beat the odds as a pilot on the river and as a player at the card table. After he retired from the river, his luck took a strange twist on August 2, 1876, when he sat at a poker table in Deadwood, South Dakota, with Wild Bill Hickok and two other players. On this day Hickok’s back wasn’t to the wall, as was his custom, and Massie apparently refused to change seats with Hickok not once, but twice. Not only that, but Massie was winning and Hickok was losing. In Hickok’s last game, as Massie laid down his winning hand, Wild Bill took an assassin’s bullet in the back of his head. The bullet exited through Hickok’s cheek and lodged in Massie’s wrist. Wild Bill’s hands still clutched his last poker hand with two pair—aces and eight—known to modern poker players as the dead man’s hand. Massie carried that bullet in his wrist for 34 years, and took it to his grave in St. Louis’ Bellfontaine Cemetery.

Massie’s good fortune at the poker table was surpassed only by his skill on the river. He could read the signs on the water’s surface—ripples, colors, stream lines—and tell whether they hid snags or obstacles, and he knew how they changed depending on weather. He memorized the river like no pilot before or since. He could navigate tricky turns like Providence Bend rounding the southwest edge of Boone County, and Plowboy Bend just below that, where the sidewheeler Plowboy sank in 1853. The townspeople of Sandy Hook built the first house in town from the ship’s cabin.

Other pilots paid Massie so they could follow his course, and sometimes he’d lead a string of six or eight boats. In 60 years of piloting, Massie sank only one boat, when the giant sternwheeler Montana hit the Wabash Bridge at St. Charles.

“Steamboat Bill” Heckman tells a story about Massie’s Montana and her sister ship, the Dacotah, in the December 30, 1939 issue of Waterways Journal. When Captain John Gonsallis hit a stump in Providence Bend and sank the Dacotah in 1884, Massie sneered: “Did Gonsollas not know an obstruction as prominent as that stump in Providence Bend?” Gonsollas responded that the stump wasn’t near as prominent as the bridge where Massie wrecked the Montana, just three months earlier.

As the sun set on the steamboating era, those great riverboat captains must have seen the paradox: to compete with the railroads, they built bigger and bigger boats. But the big boats were not as agile on the wild Missouri River, unforgiving around the shipwreck bends.