Oh, The Trumanity!

November 2017

I hadn’t expected to encounter food fit for the king. Not here, within a wedge shot of so much history. But that’s what makes the journey so rewarding.

I finished my Elvis, a peanut butter sandwich slathered with marshmallow crème and bolstered with bacon and bananas, served on grilled whole wheat. It’s a big seller at Clinton’s Soda Fountain on the Independence town square, although young Harry never sold one in his first job there, since Elvis didn’t put his first peanut butter in his diaper for decades after Harry worked there.

“Where’s the Harry Truman?” I asked my server across the counter.

She pointed to the menu on the wall. “Right there: The chocolate sundae with butterscotch.” I had one in due course. Thus fortified with the favorites of the king and the leader of the free world, I set out to scratch the surface of this historic town.

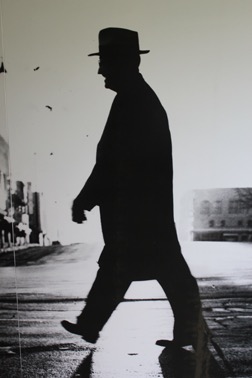

Guarding the courthouse, Truman’s statue shares the grounds with the county’s namesake, Andrew Jackson. In America there are more counties named Jackson than there are rabbits or zucchinis. This Jackson County has a wild history. Old Hickory could care less, by the looks of his statue, mounted on horseback, sitting slim and grim. He looked pissed. But Andrew Jackson always looked pissed. Today he’s pissed that he may get kicked off the $20 bill. In contrast, Harry Truman’s statue is smiling as he strikes a walking pose.

Locals saw a lot of Harry Truman.

They saw him across the street during the centennial of the old 1859 jail, its future looking squarely into a wrecking ball until Truman helped save the structure.

The Independence jail appeared on the world stage many times. Its most infamous resident was so popular among townsfolk that the jailer never locked his cell. Wanted for robbery and murder, Frank James chose to turn himself in to Governor Thomas Crittenden at the State Capitol in Jefferson City, and that odd couple rode the train west to Independence. The event was more like a homecoming than a surrender. For six months over the winter of 1882, inmate James came and went as he pleased, before he was shipped off to trial at Gallatin.

Crisscrossing downtown, I must’ve run a dozen stop signs, smiling broadly as I crossed each intersection.

“The mules are immune” to things like stop signs and traffic tickets, my guide told me as he held the covered wagon’s reins to Harry and Ed, named for two partners in a bygone local haberdashery.

Ralph Goldsmith was born for this job. He looks like he could be a member of the Cole Younger gang, whose ranks lived in this area, or maybe a wagon master among the millions of people who launched from here on the perilous journey to a new life on the western frontier.

“You know my favorite Truman quote?” he asked. I didn’t. “There’s nothing new in this world, except the history that you don’t know.”

The 30-minute wagon tour, a bargain at fifty cents a minute, sets the scene for digging deeper into the many layers of history preserved in Independence. As Ralph talked about the pioneers and the Mormons and Truman and Frank James and the origin of Bill Hickok’s wild nickname, we rode in the very ruts (swales, they’re called) formed by a hundred thousand wagons headed west. With a firm foundation of tales about the town, I thanked Ralph Goldsmith and drove a short hop to the magnificent museum called the Truman Library.

After all, there’s nothing new in this world, except the history that you don’t know.

Excerpted from John’s upcoming book, “300001, A Road Odyssey.”