Oh, The Trumanity!

November 2017

I hadn’t expected to encounter food fit for the king. Not here, within a wedge shot of so much history. But that’s what makes the journey so rewarding.

I finished my Elvis, a peanut butter sandwich slathered with marshmallow crème and bolstered with bacon and bananas, served on grilled whole wheat. It’s a big seller at Clinton’s Soda Fountain on the Independence town square, although young Harry never sold one in his first job there, since Elvis didn’t put his first peanut butter in his diaper for decades after Harry worked there.

“Where’s the Harry Truman?” I asked my server across the counter.

She pointed to the menu on the wall. “Right there: The chocolate sundae with butterscotch.” I had one in due course. Thus fortified with the favorites of the king and the leader of the free world, I set out to scratch the surface of this historic town.

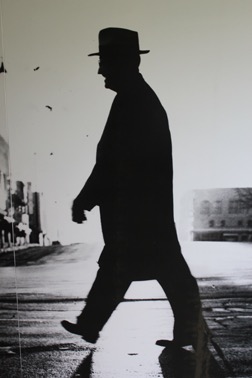

Guarding the courthouse, Truman’s statue shares the grounds with the county’s namesake, Andrew Jackson. In America there are more counties named Jackson than there are rabbits or zucchinis. This Jackson County has a wild history. Old Hickory could care less, by the looks of his statue, mounted on horseback, sitting slim and grim. He looked pissed. But Andrew Jackson always looked pissed. Today he’s pissed that he may get kicked off the $20 bill. In contrast, Harry Truman’s statue is smiling as he strikes a walking pose.

Locals saw a lot of Harry Truman.

They saw him across the street during the centennial of the old 1859 jail, its future looking squarely into a wrecking ball until Truman helped save the structure.

The Independence jail appeared on the world stage many times. Its most infamous resident was so popular among townsfolk that the jailer never locked his cell. Wanted for robbery and murder, Frank James chose to turn himself in to Governor Thomas Crittenden at the State Capitol in Jefferson City, and that odd couple rode the train west to Independence. The event was more like a homecoming than a surrender. For six months over the winter of 1882, inmate James came and went as he pleased, before he was shipped off to trial at Gallatin.

Crisscrossing downtown, I must’ve run a dozen stop signs, smiling broadly as I crossed each intersection.

“The mules are immune” to things like stop signs and traffic tickets, my guide told me as he held the covered wagon’s reins to Harry and Ed, named for two partners in a bygone local haberdashery.

Ralph Goldsmith was born for this job. He looks like he could be a member of the Cole Younger gang, whose ranks lived in this area, or maybe a wagon master among the millions of people who launched from here on the perilous journey to a new life on the western frontier.

“You know my favorite Truman quote?” he asked. I didn’t. “There’s nothing new in this world, except the history that you don’t know.”

The 30-minute wagon tour, a bargain at fifty cents a minute, sets the scene for digging deeper into the many layers of history preserved in Independence. As Ralph talked about the pioneers and the Mormons and Truman and Frank James and the origin of Bill Hickok’s wild nickname, we rode in the very ruts (swales, they’re called) formed by a hundred thousand wagons headed west. With a firm foundation of tales about the town, I thanked Ralph Goldsmith and drove a short hop to the magnificent museum called the Truman Library.

After all, there’s nothing new in this world, except the history that you don’t know.

Excerpted from John’s upcoming book, “300001, A Road Odyssey.”

300001: A Road Odyssey

August 2017

You wouldn’t pick her for World’s Greatest Car.

Her headlamps have filmy cataracts. Her doors are dented, and she suffered the insult of a salvage title after her complexion was pocked by a hailstorm. She smells of antifreeze. Her transmission whines. Her brakes squeal.

But she’s a keeper.

I met her in a car lot 17 years ago. She was sleek and new and lipstick red, and even though I didn’t realize it at the time, she would set course on a journey no other car has made; she’s driven every mile of every road on Missouri’s highway map.

Her name reflects the auto company that built her, a company that folded and faded in the rearview mirror, leaving Erifnus Caitnop to fend for herself. Yet she remains strong, reaching an age when 99 percent of her peers have been pounded into refrigerator magnets.

With little planning, Erifnus and I began a string of shortcuts that lasted beyond a dozen years, a journey that left our tire tracks along every inch of state-maintained pavement, every county road from AA to ZZ, plus thousands of miles of gravel and dirt.

This 1999 Pontiac Sunfire became my Trigger, my Lassie, my Old Faithful. She’s dauntless on dirt roads and fearless beside 40-ton truckships. She’s crossed Skull Lick Creek and Rabbit Head Creek. She’s climbed Long Tater Hill, descended to Devil’s Well and the Little Grand Canyon and three Toad Sucks. Oh, and the Garden of Eden.

She’s witnessed OcToasterFest and the Testicle Festival, and a mineral springs with two iron pipes that deliver separate healing waters to Democrats and Republicans.

She’s outlived the company that made her. But I wouldn’t trade her for the Mona Lisa.

This car won an Emmy. Oh, I went along for the ride, but the car was the star of the show.

Erifnus doesn’t care. Even as she nurses a small patch of rust beneath her passenger door, she’s a workhorse, performing flawlessly, for the most part. Blame her brushes with danger on driver error.

I drove into danger because I was curious. Erifnus did it because she had no choice. But she’s a gymnast, handling like a thoroughbred through curves and mud, dodging texters and tweeters and road ragers and drunks and texters and squirrels, dogs, cats and deer and terrapins and texters. We’ve slid sideways in sleet, jumped curbs and low-water crossings. We’ve passed every pun on every roadside marquee, every time-and-temperature sign, every clip joint and carny barker and corn dog vendor, every barbecue shack and taco stand.

And we’ve stopped at most of ’em.

That’s why I should’ve planned better when her milestone sneaked up on us as we left hometown Columbia’s city limits. We pulled off I-70 and into a parking lot, where I made Erifnus Caitnop turn in circles until she reached 300,000 miles. It was an insensitive thing to do to an old horse who has served so well. But I wanted photos...and not on the shoulder of I-70.

During our short celebratory detour, I-70 had backed to a standstill. So Erifnus did what she does best: hit the backroads. Blacktops to Millersburg through Mark Twain’s deep forest past Tonanzio’s tables where in a different millennium we feasted like Bacchus. We passed white-fenced farms raising white-faced horses, followed a river that led past Dan’l Boone’s grave and a dozen vineyards. We reached our destination late, with more stories than a barrel o’ bards/troubadours.

Come to think of it, we got a good start on 400,000.

John Robinson is considering one of two titles for his upcoming book: 1) Pioneers Need Pants and Other Stories from the Road or 2) 300001: A Road Odyssey. Which do you like? Read more of the author’s stories at JohnDrakeRobinson.com.

Channeling Jack's Ghost

May 2017

A young Shawnee Indian boy stowed away on a packet steamer headed down the Ohio River in 1811. As the boat reached the Mississippi and started south, the New Madrid Earthquake turned the waters backward and wrecked the steamer, pinning the captain in the wreckage. The boy, nicknamed Jack, freed the captain, and for the kid’s bravery, the skipper gave his captain’s cap to Jack.

After a career on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, Captain Jack settled along the river that eventually took his name: the Jacks Fork. Always wearing his cap, Jack became a fixture on the river. For decades, day and night, summer and winter, he poled his john boat up and down the river. He was a bit mysterious, but he looked official in his captain’s hat.

Today Jack’s spirit warns floaters, even experienced floaters, that this river—any river—can be tricky.

They’re about to become trickier.

Come mid-summer, floaters may lose a key river tool. The tool isn’t something you buy at the Jiffymart with beer and snacks.

It’s a gauge—one of 49 gauges that measure our rivers in key spots. These gauges—operated by the United States Geological Service—have saved countless lives by reporting water volume and river levels to your smart phone. Smart floaters use these gauges. Combined with weather forecasts, the gauges can help plan a safer experience on the river and help avoid high-water tragedy and low-water trudgery. Gauges inform floaters on the Current River, the Jacks Fork, Eleven Point, Meramec, Huzzah, Little Piney and the Big and Little Niangua Rivers.

Avoiding float trip tragedy is only one purpose for these stream gauges. Beyond these Ozark float streams, the same type gauges are on many rivers for a different reason. They provide data for managing drinking water and timing wastewater discharges and reservoir releases, irrigation, even power plants. They’re used to manage habitat. They help design bridges and levees and dams.

But current funding for these 49 USGS gauges in Missouri will end June 30. Unless other funding sources are identified, the information from these gauges will no longer be available.

If you’re a Navy Seal, you probably feel secure without these reports. If you’re a mother sending your kid into the unknown, you may not be so sure.

Figures from the USGS indicate that one gauge costs about $15,000 to operate for a year. If a gauge is removed a re-install would add about $15,000.

Writer, geologist and hydrology expert Jo Schaper compares “rivers without gauging stations to roads without traffic signals. You could still use the roads, but the risk would be much greater.”

Former Missouri Department of Natural Resources Environmental Specialist Sharon Clifford brings up another issue. As MDNR’s first coordinator to monitor our streams’ Total Daily Maximum Loads, Clifford recalls that “40 states were sued over this issue. It’s about fixing waterways that don’t meet standards after all permits are issued, and it’s part of the Clean Water Act. To calculate a TMDL, you must have good flow information to plug into the model. Without it, it isn’t possible to do it accurately. So what now? More lawsuits? Huge waste of tax payer dollars.”

It’s like driving a car without a gas gauge.

Your mechanic has a phrase for it: “You can pay me now, or you can pay me later.”

Listen to your mechanic. Contact your state and federal representatives and tell them to keep the river gauges.

It might save a soul from joining the ghost of Captain Jack.

Read more of the author’s stories at JohnDrakeRobinson.com. His previous books, Coastal Missouri and A Road Trip Into America’s Hidden Heart are available at independent bookstores and online booksellers everywhere.

Churchill, Church & Charm

February 2017

No doubt about it, Beks knows how to serve up sumptuous fare inside the warm ambiance of this charming restaurant in the historic Brick District of Fulton. So Erifnus beat a path to the Brick District and let me graze. I’d had the sliders before, so today the black and blue tilapia jumped off the menu, blackened with bleu cheese crumbles.

Across the old brick street from Beks, the tailor to your brain beckons. Well Read Books, an independent bookstore, fills its 120-year-old space with book smells and good light, easychairs and cats.

Fulton tells a good story. It’s the setting for a pair of dramatic portrayals by the world’s two top conservative icons. Ronald Reagan calls King’s Row his best movie. Filmed in 1942, it’s a fictional story about folks in Fulton. Four years later, Winston Churchill delivered his Iron Curtain Speech on the campus of Fulton’s Westminster College and set in motion the American visual of the Cold War, which consumed the attention of an octet of presidents, including Reagan.

The Winston Churchill National Museum sits in the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Aldermanbury. The old church gets around. It was built nearly 900 years ago in the middle of London. Sir Christopher Wren redesigned the chapel after the 1666 Great Fire of London gutted its interior. The blitzkriegs of 1941 destroyed the old church, again. But it survived enough that in the mother of all pilgrimages, loving hands picked up the church, jumped the pond and plopped it down in Fulton. They disassembled and reassembled it using a numbering system that’s part paint-by-number, part Rubik’s Cube. Having undergone a facelift worthy of Wren, the church houses a museum celebrating Churchill’s life and achievements. Outside sits just enough of the Berlin Wall to give you a creepy feel for the reality of the Cold War standoff.

In a way, this place has become the American Westminster Abbey—without all the dead bodies. But it’s real, and presented tastefully. Before the old church made its big leap, before the tragic fire and the awful bombs, it was the place where William Shakespeare prayed for good reviews and where John Milton got married. I think Milton talks about his marriage in his autobiography, Paradise Lost. Maybe not. During an earlier visit to Fulton, I searched in vain throughout the college for a Paradise Lost and Found. The Kingdom holds no such treasure.

The town also treasures its most famous resident that nobody talks about. Henry Bellamann was born and raised in Fulton, and when he moved away to teach music at Julliard and Vassar, he dabbled in psychology and poetry. But his lasting legacy is a dark description of psychological terror and taboo, the seed for the modern soap opera. It’s the novel, King’s Row–the same book that later boosted Ronald Reagan’s career—about a small town with whitewashed fences and whitewashed reputations hiding dirty little corners and the seamy underbelly of its residents’ obsessions with money and status, class and racism, sex and sadomasochism, profit and plunder, and a cornucopia of mental afflictions.

The novel begins by advising readers that the story is fictional and could be about any town anywhere. To be fair, that statement is true. But there’s little doubt that Bellamann’s setting is Fulton. In the acutely sanitized movie adaptation of the book, Ronald Reagan received accolades for his performance. But the movie bears little resemblance to the novel’s deep disturbing Dostoyevsky-like themes and subplots. Literary critics call this book the blueprint for Peyton Place—and every soap opera since.

The above is an excerpt from John Robinson’s third book, Pioneers Need Pants, to be published in 2017. Read more of the author’s stories at JohnDrakeRobinson.com. His previous books, Coastal Missouri and A Road Trip Into America’s Hidden Heart are available at independent bookstores and online booksellers everywhere.